|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If you have trouble viewing this newsletter, click here. Welcome again to our monthly newsletter with features on exciting celestial events, product reviews, tips & tricks, and a monthly sky calendar. We hope you enjoy it!

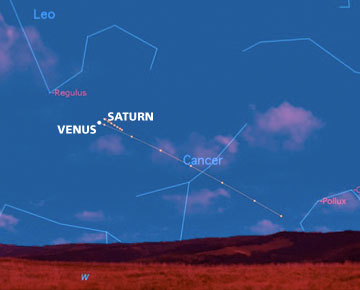

Whether you are a beginner or a seasoned "pro," summer offers a wealth of sky sights. Here are just a handful of easy targets, but be sure to check out your copy of Starry Night® and stayed tuned here on Space.com for more suggestions as the summer sails by. The early evening offers three easy planets. Venus continues to dominate the western sky, with Saturn nearby in Leo. On June 18, the Crescent Moon, Saturn and Venus make a wonderful sight in the western twilight, a great target for binoculars such as Orion's Resolux WP 7x50s.

Figure 1—Look west at 9:00 PM Eastern Time, June 18, 2007 If you miss it, there is a similar grouping on July 16. To the southeast, Jupiter is a standout near Antares in Scorpius, but you'll need a scope to see the nightly parade of moons. (The Orion ED refractor line is a good choice for Jupiter, Saturn's rings, the Moon and planets in general.) Jupiter just gets better through the Summer, but Venus and Saturn will be gone by August, lost in the glare of the setting Sun. Strictly speaking, it isn't a constellation, but don't miss the "Big Dipper," high overhead but dipping to the northwest as the hours (and the Summer) go on. To help locate two bright stars, follow the curve of the Big Dipper's handle downward to Arcturus and then on to Spica. You'll be "arcing to Arcturus and speeding on to Spica." Midway between the bright stars Arcturus and Vega is the faint constellation named for the mythological strongman, Hercules. The constellation is faint, but contains one of the sky's gems, a magnificent globular cluster called M13. You can pick it out as a fuzzy "star" in binoculars, but you'll want a real light bucket, such as an Orion SkyQuest Dobsonian, to catch this cluster's glittering diamonds.

Figure 2—M13 in Hercules and M57 The Ring Nebula in Lyra A slightly harder Summer target is the "Ring" nebula, M57 in Lyra, not far from the bright star Vega. Smaller scopes may show M57 as a faint, fuzzy and elliptical-shaped "ghost," but you'll need a six-inch or greater objective (for example, an Orion AstroView EQ reflector) to get a good view of the ring structure. But once seen, it is never forgotten. You should also check out Lyra's famed "double-double" star, Epsilon, which is best viewed in a refractor. In mid to late Summer, you'll want to identify the "Summer Triangle" made up of the stars Vega, Altair and Deneb. Close to Deneb is a large, loose open cluster called M39. Use binoculars or better, a low-power Dobsonian. And while you are at it, try finding the "North American" nebula, just about three degrees from Deneb. This is visible to the unaided eye under exceptional conditions, but usually you'll need at least a good pair of binoculars. Also from a very dark location, you can see the heaven's twinkling river, the Milky Way, crossing straight through the Summer Triangle. Galileo was the first to realize that the Milky Way is made of stars, an observation you can recreate with a good pair of binoculars. Meanwhile, Jupiter is blazing in the South, near Scorpius, a region with too many star clusters and nebulosities to mention. Scan the area with binoculars, following up with views through a Dobbie or low power reflector scope. By late summer, the Milky Way is complemented by our nearest major galactic neighbor, the magnificent Andromeda Galaxy, M31. Under good, dark conditions, you should be able to spot this with the unaided eye, a faint oblong smudge looking like a small part of the Milky Way that has broken off. But in reality it is a major galaxy, larger than the Milky Way, with hundreds of billions of stars and more than two million light years away. M31 is one of the farthest objects visible to the unaided human eye. When you view the Andromeda Galaxy, whether with just your eye or binoculars or perhaps a nice Dobsonian, you are peering more than two million years in the past. Now that is an amazing thought to ponder on a warm Summer evening! Larry Sessions

When June begins, Venus and Saturn will be nearly 25° apart, Venus close to Pollux in Gemini and Saturn close to Regulus in Leo. Oven the month of June, we will witness the spectacle as the brilliant Venus swiftly crosses the entire constellation of Cancer until the two meet, close to Regulus, at the beginning of July.

Figure 1—Paths of Venus and Saturn, June 1 to July 1, 2007 In the Starry Night® image above, we see the paths of the two planets from June 1 to July 1, each dot marking five days along the planets’ paths. Because Saturn is 19 times farther away from us than Venus, 9.94 versus 0.53 astronomical units from Earth, it moves much more slowly against the background stars. Thus Venus appears to catch up with Saturn and pass it on July 1. A particular date to watch is June 18, when the four-day-old crescent Moon will be located right in between Saturn and Venus. Soon after its close approach to Venus, Saturn will disappear into the Sun’s glare, while Venus continues to grow brighter until in reaches maximum brilliancy on July 12. Then it too disappears into the Sun’s glare but it will pass between us and he Sun, while Saturn is passing behind the Sun. This so called inferior conjunction of Venus will take place on August 18, Venus passing 8 degrees south of the Sun. Saturn’s conjunction with the Sun comes three days later, on August 21. As the image below from Starry Night® shows, the Sun, Venus, and Saturn will be joined by Mercury and Regulus for a quintuple conjunction! Normally this would be invisible to us unless there happened to be a solar eclipse on that date, but the LASCO C3 images on the SOHO Web site should enable us all to witness this wonderful grouping:

Figure 2—Conjunction of August 21, 2007 One thing to watch during these events is Venus’ size and phase. On June 1 it will be a smallish disk, 22 arcseconds in diameter, very slightly gibbous (54% illuminated). On July 1, when it’s in conjunction with Saturn, it will have grown in size to 32 arcseconds, but it will have shrunk to a crescent only 35% illuminated. At greatest brilliancy on July 12, it will be 38 arcseconds in diameter and 26% illuminated. At inferior conjunction on August 18, it will be a whopping 58 arcseconds and 1% illuminated! I once observed Venus within a-day-and-a-half of inferior conjunction, and saw something similar to the diamond ring effect in a solar eclipse: the entire ring of the atmosphere of Venus was backlit by the Sun. Trying to observe Venus this close to the Sun is very dangerous, especially this year as Venus will be below the Sun in the sky. When I observed it, it was north of the Sun, so the Sun could be safely blocked by a convenient rooftop. From about the beginning of July onward, the crescent phase of Venus will be visible in ordinary binoculars. This makes a challenging observing project and I encourage you to try to follow Venus with binoculars over the next two months. There also will be some wonderful opportunities for photography of the encounter with ordinary cameras. Geoff Gaherty

The moon is the hardest working object in the night sky. Unlike the planets that hide close to the sun for months and wallow in the lowest reaches of the ecliptic for years at a time—the moon is always there for you. It is beautifully positioned for picture taking much of each month. And during those brief times when it lies behind the sun you can always spend some hours at the eyepiece looking for dim fuzzy stuff! Through a telescope, the moon is more fun than Google Earth. As you zoom in with higher magnification new landscapes are revealed and a limitless supply of features—craters, rimae, domes—are revealed. To capture a detailed close-up of the moon using a long effective focal length you will need a telescope and a mount that tracks the night sky. A camera capable of capturing streaming video (a webcam or dedicated planetary imaging camera) is relatively inexpensive, simple to set up in the field and perfectly suited for lunar imaging at high power. A basic 640x480 pixel chip is fine. Larger chips will display a wider field of view but will be more expensive and require a fast processor to handle the huge stream of data at 30 or 60 frames per second.

Like a trip to the Louvre, the moon at high power will offer more than you can see in one visit. It pays to plan ahead. Your session will be most rewarding on a night when the seeing is steady. Find a good weather resource (the Clear Sky Clock is a good internet site to bookmark) and learn the patterns at your location. Often you will find windows of good seeing just after sunset and before sunrise. Store your telescope in an unheated location so it will be thermally stable and ready for imaging at short notice. Don't forget to practice with your imaging set-up in the daytime. Settings for gain, shutter and gamma can be confusing. You don't want to be figuring this out in the dark as a patch of perfect seeing drifts overhead. Learn to interpret the histogram in your camera's capture software and use it to guide your exposure. Too often an image that looks great on screen in the dark of night is badly underexposed when viewed the next day. Planetarium software like Starry Night® or the on-line resources at Space.com help you to plan ahead by showing which lunar features will be visible on any day in any year. I always start a lunar imaging session with some relaxed observing at moderate power. This gives me a sense of the seeing and a first hand look at the features best placed that night. I choose my magnification (adjusting the native focal length of my scope with various barlows) based on this visual assessment. I check my mount tracking too. You don't need a dead nuts polar alignment, but if you have significant drift during capture you will have to crop the image down later on. Even large lunar craters will fit in the field of a small webcam chip at high magnification. Crater portraits are a great place to get your feet wet. Stepping out to a wider field of view can create a stunning panorama. This can be accomplished by reducing the magnification (a good plan if the seeing is poor) or by moving the camera and taking several adjoining streams to be combined later into a large mosaic. Study the area around a prominent feature by panning the mount to plan your composition. When preparing a mosaic, I like to orient the camera so that the keypad buttons move the mount horizontally and vertically through my intended mosaic field. This helps me to minimize gaps in data and voids in the final assembled picture. A color filter in the light path will magically help stabilize the seeing. A red filter is the most effective in fair to average conditions and is used by most serious lunar imagers. If the seeing is good, try a green filter. It will provide a similar effect with improved resolution over the red. The moon is such a rich subject—where to begin filming?! The eye is always drawn to the lunar terminator, where contrast between shadows and sunlit highlights are most dramatic. Here subtle changes in surface elevation are accentuated; molehills become mountains. While this is a great location to scout for photo opportunities, images captured in the line between lunar night and day can be notoriously difficult to process. Consider moving away from the terminator to an area of higher sun angle. Pictures centered here will have a wide dynamic range that stands up well to contrast enhancement with image processing tools such as unsharp mask. Images that include the lunar limb and the blackness of space can also be spectacular, giving a sense of perspective and that "coming in for a landing" feeling. The edges of lunar maria, where smooth, dark, craterlet pocked volcanic floes abut rugged lunar highlands, are another excellent choice. You can quickly get lost in the wealth of lunar detail, filling all available space in your computer hard drive before you know it. To me, a stash of great lunar video is money in the bank, to be saved and savored during those rainy days when image processing is the only astronomy activity possible. A portable hard drive is good insurance that you will run out of night before you run out of memory. Lunar imaging today is undergoing a renaissance as new cameras and processing techniques yield images of incredible resolution and realism. If you find yourself bitten by the bug, I would recommend a copy of the gorgeous new edition of the Atlas of the Moon by Antonin Rukl. A Web search will bring up many excellent resources–including searchable databases of Apollo mission images that are archived for research. Perhaps the most enjoyable of all is LPOD (the Lunar Picture of the Day). Here you'll find the finest amateur and professional images annotated with fascinating copy by Dr. Charles Wood. It's been updated every day for years and hasn't run out of craters yet! Alan Friedman

Rich Cambell of Orion Telescopes & Binoculars was interviewed by "News In Space" host Casey Dee at a recent Astronomy Expo in Suffern, New York. Courtesy AstroShorts.com Pedro Braganca

At this time of year, Coma Berenices hangs high overhead, very well-placed for observation. Berenice was an Egyptian queen, the wife of King Ptolemy III Euergestes. When her husband went off to war, to ensure his safe return, she promised her hair to Aphrodite. The King did indeed return and Berenice gave up her hair, a tuft of which became this constellation. Diadem is a binary star about 47 lightyears from us. It's two suns cannot be split in telescopes but, just a little to the north, M53 hangs in space at a much greater distance: 60,000 lightyears. M53 is a halo cluster, filled with dozens of Mag 13 stars. M64, The Blackeye Galaxy, gets its famous name from the dark dust lane that cuts through the galaxy's core. With averted vision, you'll just be able to make out the lane. Overall, the galaxy is bright enough to be visible in binoculars. NGC 4725 is a large bright spiral galaxy which has been warped by its interactions with close-by NGC 4747. This patch of sky also contains the North Galactic Pole. NGC 4559, a faint spiral galaxy, is inclined 20° from edge-on. The larger your scope the better the view. NGC 4565 is inclined only 4° from edge-on and is breath-taking. Both galaxies belong to the Virgo Cluster. NGC 4494 is an elliptical galaxy whose core rotates very rapidly—and in the opposite direction to the stars in the outer disk! Sean O'Dwyer

Horse Head Nebula

PRIZES AND RULES: We would like to invite all Starry Night® users to send their quality astronomy photographs to be considered for use in our monthly newsletter.

Please read the following guidelines and see the submission e-mail address below.

|

June 2007

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

You have received this e-mail as a trial user of Starry Night® Digital Download

or as a registrant at starrynight.com. To unsubscribe, click here.